- Home

- Jeffrey Archer

A Prison Diary Page 11

A Prison Diary Read online

Page 11

8.00 pm

I’ve just finished checking over my script for the day when my cell door is opened by an officer. Fletch is standing in the doorway and asks if he can join me for a moment, which I welcome. He takes a seat on the end of the bed, and I offer him a mug of blackcurrant juice. Fletch reminds me that he’s a Listener, and adds that he’s there if I need him.

The Listeners

Who are they?

How do I contact them?

How do I know I can trust them?

Listeners are inmates, just as you are, who have been trained by the Samaritans in both suicide awareness and befriending skills.

You can talk to a Listener about anything in complete confidence, just as you would a Samaritan. Everything you say is treated with confidentiality.

Listeners are rarely shocked and you don’t have to be suicidal to talk to one. If you have any worries or concerns, however great or small, they are there for you. If you have concerns about a friend or cellmate and feel unable to approach a member of the spur staff or healthcare team, then please tell a Listener in confidence. It is not grassing and it may save a life.

Listeners are easy to contact. Their names are displayed on orange cards on their cell doors and on most notice boards throughout the House-Blocks or ask any member of the spur staff.

Listeners are all bound by a code of confidentiality that doesn’t only run from House-Block to House-Block but also through a great number of Prisons throughout the country. Any breach of that confidentiality would cause irreparable damage to the benefits achieved, and because of this code Listeners are now as firmly established as your cell door.

He then begins to explain the role of Listeners and how they came into existence after a fifteen-year-old boy hanged himself in a Cardiff jail some ten years ago. He passes me a single sheet of paper that explains their guidelines. Among Fletch’s responsibilities is to spot potential bullies and – perhaps more important – potential victims, as most victims are too frightened to give you a name because they fear revenge at a later date, either inside or outside of prison

I ask him to share some examples with me. He tells me that there are two heroin addicts on the spur and although he won’t name them, it’s hard not to notice that a couple of the younger lifers on the ground floor have needle tracks up and down their arms. One of them is only nineteen and has tried to take his own life twice, first with an overdose, and then later when he attempted to cut his wrist with a razor.

‘We got there just in time,’ says Fletch. ‘After that, the boy was billeted with me for five weeks.’

Fletch feels it’s also vitally important to have a good working relationship with the prison staff – he doesn’t call them screws or kangaroos – otherwise the system just can’t work. He admits there will always be an impenetrable barrier, which he describes as the iron door, but he has done his best to break this down by forming a prison committee of three inmates and three officers who meet once a month to discuss each other’s problems. He says with some considerable pride that there hasn’t been a serious incident on his spur for the past eight months.

He then tells me a story about an occasion when he was released from prison some years ago for a previous offence. He decided to call into his bank and cash a cheque. He climbed the steps, stood outside the bank and waited for someone to open the door for him. He looks up from the end of the bed at the closed cell door. ‘You see, it doesn’t have a handle on our side, so you always have to wait for someone to open it. After so long in prison, I’d simply forgotten how to open a door.’

Fletch goes on to tell me that being a Listener gives him a reason for getting up each day. But like all of us, he has his own problems. He’s thirty-seven, and will be my age, sixty-one, when he is eventually released.

‘The truth is that I’ll never see the outside world again.’ He pauses. ‘I’ll die in prison.’ He pauses again. ‘I just haven’t decided when.’

Fletch has unwittingly made me his Listener.

Day 11

Sunday 29 July 2001

6.27 am

Sundays are not a good day in prison because you spend so much time locked up in your cell. When you ask why, the officers simply say, ‘It’s because we’re short-staffed.’ I can at least use six of those hours writing.

Many of the lifers have long-term projects, some of which I have already mentioned. One is writing a book, another taking a degree, a third is a dedicated Listener. In fact, although I may have to spend most of today locked up in my cell, Fletch, Billy, Tony, Paul, Andy and Del Boy all have responsible jobs which allow them to roam around the block virtually unrestricted. This makes sense, because if a prisoner has a long sentence, they may feel they have nothing to lose by causing trouble, but once you’ve given them privileges – and not being locked up all day is unquestionably a privilege – they’re unlikely to want to give up that freedom easily.

8.03 am

I shave using a Bic razor supplied by HMP. They give you a new razor every day, and it is a punishable offence to be found with two of them in your cell, so every evening, just before lock-up, you trade in your old one for a new one.

As soon as the cell door is opened, I make a dash for the shower, but four young West Indians get there before me. One of them, Dennis (GBH), has the largest bag of toiletries I have ever seen. It’s filled with several types of deodorant and aftershave lotions. He is a tall, well-built, good-looking guy who rarely misses a gym session. When I tease him about the contents of his bag, Dennis simply replies, ‘You’ve got to be locked up for a long time, Jeff, before you can build up such a collection on twelve-fifty a week.’ Another of them eventually emerges from his shower stall and comments about my not having flipflops on my feet. ‘Quickest way to get verrucas,’ he warns me. ‘Make sure Mary sends you in a pair as quickly as possible.’

Having repeatedly to push the button with the palm of one hand while you soap yourself with the other is a new skill I have nearly mastered. However, when it comes to washing your hair, you suddenly need three hands. I wish I were an octopus.

When I’m finally dry, my three small thin green prison towels are all soaking – I should only have one, but thanks to Del Boy…I return to my cell, and because I’m so clean, I’m made painfully aware of the prison smell. If you’ve ever travelled on a train for twenty hours and then slept in a station waiting room for the next eight, you’re halfway there. Once I’ve put back on yesterday’s clothes, I pour myself another bowl of cornflakes. I think I can make the packet (£1.47) last for seven helpings before I’ll need to order another one. I hear my name being bellowed out by an officer on the ground floor, but decide to finish my cornflakes before reporting to him – first signs of rebellion?

When I do report, Mr Bentley tells me that there’s a parcel for me in reception. This time no one escorts me on the journey, or bothers to search me when I arrive. The parcel turns out to be a plastic bag full of clothes sent in by Mary: two shirts, five T-shirts, seven pairs of pants, seven pairs of socks, two pairs of gym shorts, a tracksuit, and two sweaters. The precise allocation that prison regulations permit. Once back in my cell I discard my two-day-old pants and socks to put on a fresh set of clothes, and now not only feel clean, but almost human.

I spend a considerable time arranging the rest of my clothes in the little cupboard above my bed and as it has no shelves this becomes something of a challenge.* Once I’ve completed the exercise, I sit on the end of the bed and wait to be called for church.

10.39 am

My name is among several others bellowed out by the officer at the front desk on the ground floor, followed by the single word ‘church’. All those wishing to attend the service report to the middle landing and wait by the barred gate near the bubble. Waiting in prison for your next activity is not unlike hanging around for the next bus. It might come along in a few moments, or you may have to wait for half an hour. Usually the latter.

While I’m standing there, Fletch joins

me on the second-floor landing to warn me that there’s an article in the News of the World suggesting that I’m ‘lording it’ over the other prisoners. Apparently I roam around in the unrestricted areas in a white shirt, watching TV, while all the other prisoners are locked up. He says that although everyone on the spur knows it’s a joke, the rest of the block (three other spurs) do not. Fletch advises me to avoid the exercise yard today, as someone might want ‘to make something of it’.

The more attentive readers will recall that my white shirt was taken away from me last week because I could be mistaken for an officer; my feeble attempt to watch cricket on TV ended in having to follow the progress of the King George and Queen Elizabeth Stakes; and by now all of you know how many hours I’ve been locked in my cell. How the News of the World can get every fact wrong surprises even me.

The heavy, barred gate on the middle floor is eventually opened, and I join prisoners from the other three spurs who wish to attend the morning service. Although everyone is searched, they now hardly bother with me. The process has become not unlike going through a customs check at Heathrow. There are two searchers on duty this morning, one male and one female officer. I notice the queue to be searched by the woman is longer than the one for the man. One of the lifers whispers, ‘They can’t add anything to your sentence for what you’re thinking.’

When I enter the chapel I return to my place in the second row. This time the congregation is almost 80 per cent black, despite the population of the prison being around fifty-fifty. The service is conducted by a white officer from the Salvation Army, and his small band of singers are also all white. When I next see Mr Powe, I must remember to tell him how many churches, not so far away from Belmarsh, have magnificent black choirs and amazing preachers who encourage you to cry Alleluia. Something else I learnt when I was candidate for Mayor.

This week I notice that the congregation is roughly split in two, with a sort of demarcation zone about halfway back. The prisoners seated in the first eight rows have only one purpose – to follow every line in the Bible that the Chaplain refers to, to sing at the top of their voices and participate fully in the spirit of the service. The back nine rows show scant interest in proceedings, and I observe that they have formed smaller groups of two, three or four, their heads bowed deep in conversation. I assume they’re friends from different spurs and find the service one of the few opportunities to meet up, chat, and pass on messages. Quite possibly even drugs – if they are willing to go through a fairly humiliating process.*

The Chaplain’s text this Sunday comes from the Gospel of St John, and concentrates in particular on the prodigal son. Last week it was Cain and Abel. I can only assume that next week it will be Honour Among Thieves.

The Chaplain tells his flock that he is only going to speak to them for five minutes, and then addresses us for twelve, but to be fair, he was quite regularly interrupted with cries of ‘Alleluia’, and ‘Bless us, Lord’. The Chaplain’s theme is that if you leave the bosom of your family, try to make it alone, and things go wrong, it doesn’t mean that your father won’t welcome you back if you are willing to admit you’ve made mistakes. Many of those in the front four rows start jumping up and down and cheering.

After the service is over, and we have all been searched again, I’m escorted back to House Block One, but not before several inmates from Block Three come across to say hello. Remember Mark, Kevin and Dave? I’m brought up to date with all of their hopes and expectations as we slowly make our way back to our separate blocks. No one moves quickly in prison, because it’s just another excuse to spend more time out of your cell. As I pass the desk at the end of my spur, I spot a pile of Sunday newspapers. The News of the World is by far the most popular, followed by the Sunday Mirror, but there is also quite a large order for the Sunday Times.

When I return to my cell, I find my room has been swept and tidied, and my bed made up with clean sheets. I’m puzzled, because there was nothing in the prison handbook about room service. I find out later that Taal (Ghanaian, murder, lifer) wants to thank me for helping him write a letter to his mother. Returning favours is far more commonplace in prison than it is outside.

12 noon

Lunch: grated cheese, a tomato, a green apple and a mug of Highland Spring. I’m running out of water and will in future have to order more bottles of Highland Spring and less chocolate from the canteen.

After lunch I sit down to write the second draft of this morning’s script, as I won’t be let out again until four, and then only for forty-five minutes. I clean my glasses and notice that without thinking, I’ve begun to split my double Kleenex tissue so that I can make the maximum use of both sheets.

4.00 pm

Association. During the hour break, I don’t join the others in the yard for exercise because of the News of the World article, which means I’ll be stuck inside all day. I can’t remember the last time I remained indoors for twenty-four hours.

I join Fletch (murder) in his cell, along with Billy (murder) and Tony (marijuana only, escaped to Paris). They’re discussing in great detail an article in the Sunday Times about paedophiles, and I find myself listening intently. Because on this subject, as in many others concerning what goes on in prison, I recall Lord Longford’s words, ‘Don’t assume all prisoners have fixed views.’ I feel on safer ground when the discussion turns to the Tory Party leadership. Only Tony, who reads The Times, can be described as a committed liberalist. Most of the others, if they are anything, are New Labour.*

They all agree that Ken Clarke is a decent enough sort of bloke – pint at the local and all that, and not interested in his appearance, but they know very little about Iain Duncan Smith, other than he comes from the right wing of the Party and therefore has to be their enemy. I suggest that it’s never quite that simple. IDS has clear views on most issues, and they shouldn’t just label him in that clichéd way. He’s a complex and thoughtful man – his father, I remind them, was a Second World War hero, flying Spitfires against the Germans and winning the DSO and Bar. They like that. I suspect if we were at war now, his son would be doing exactly the same thing.

‘But he has the same instincts as Ann Widdecombe,’ says Fletch. ‘Bang ’em up and throw away the key.’

‘That may well be the case, but don’t forget Ann is supporting Ken Clarke, despite his views on Europe.’

‘That doesn’t add up,’ says Billy.

‘Politics is like prison,’ I suggest. ‘You mustn’t assume anything, as the exact opposite often turns out to be the reality.’

5.00 pm

‘Back to your cells,’ bellows a voice.

I leave the lifers and return to my cell on the top floor to be incarcerated until nine tomorrow morning – sixteen hours. Think about it, sixteen hours. That’s the length of time you will spend between rising in the morning and going to bed at night.

Just as I arrive at my door, another lifer (Doug) hands me an envelope. ‘It’s from a prisoner on Block Two,’ he says. ‘He evidently told you all about it yesterday when you were in the exercise yard.’ I throw the envelope on the bed and switch on the radio, to be reminded that it’s the hottest day of the year (92°). I open my little window to its furthest extent (six inches) to let in whatever breeze there is, but I still feel myself sweating as I sit at my desk checking over the day’s script. I glance up at the cupboard behind my bed, grateful for the clean clothes that Mary sent in this morning.

6.00 pm

Supper. I can’t face the hotplate, despite Tony’s recommendation of Spam fritter, so I have another portion of grated cheese, open a small tin of coleslaw (41p) and – disaster – finish the last drop of my last bottle of Highland Spring. Thank heavens that it’s canteen tomorrow and I’m allowed to spend another £12.50.

During the early evening, I go over my manuscript, and as there are no letters to deal with, I turn my attention to the envelope that was handed to Doug in the yard. It turns out to be a TV script for a thirty-minute pilot set in a wom

en’s prison. It’s somehow been smuggled out of Holloway and into Belmarsh (no wonder it’s easy to get hold of drugs). The writer has a good ear for prison language, and allows you an interesting insight into life in a women’s prison, but I fear Cell Block H and Bad Girls have already done this theme to death. It’s fascinating to spot the immediate differences in a women’s prison to Belmarsh. Not least the searching procedure, the fact that lesbianism is far more prevalent in female prisons than homosexuality is in male establishments, and, if you can believe it, the level of violence is higher. They don’t bother waiting until you’re in the shower before they throw the first punch. Anywhere, at any time, will do.

It’s a long hot evening, and I have visits from Del Boy, Paul, Fletch and finally Tony.

Tony (hotplate, marijuana only, escaped to Paris) started life as a B-cat prisoner, and was transferred after three and a half years to Ford Open (first offence, no history of violence). After eight blameless months they allowed him out on a town visit, so he happily set off for Bognor Regis. But after four visits to that seaside resort during the next four months, he became somewhat bored with the cold, deserted beach and the limited shopping centre. That’s when he decided there were other towns he’d like to visit on his day off.

When they let him out the following month, he took the boat-train to Paris.

The prison authorities were not amused. It was only when he moved on to Spain, two years later, that they finally caught up with him and he was arrested. After spending sixteen months in a Spanish jail waiting to be deported (canteen, fifty pounds a week, and no bang-up until nine), they sent him back to the UK. Tony now resides in this high-security double A-Category prison, from where no one has ever escaped, and will remain put until he has completed his full sentence (twelve years). No time was added to his sentence, but there will be no remission (half off for good behaviour) and he certainly won’t be considered for an open prison again. This fifty-four-year-old somehow keeps smiling and even manages to tell his story with self-deprecating humour.

A Matter of Honor

A Matter of Honor Four Warned

Four Warned A Quiver Full of Arrows

A Quiver Full of Arrows Not a Penny More, Not a Penny Less

Not a Penny More, Not a Penny Less To Cut a Long Story Short

To Cut a Long Story Short The Gospel According to Judas by Benjamin Iscariot

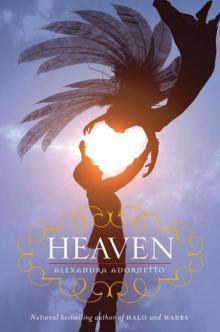

The Gospel According to Judas by Benjamin Iscariot Heaven

Heaven First Among Equals

First Among Equals Purgatory

Purgatory Kane and Abel

Kane and Abel Honor Among Thieves

Honor Among Thieves Shall We Tell the President?

Shall We Tell the President? The Prodigal Daughter

The Prodigal Daughter False Impression

False Impression Paths of Glory

Paths of Glory A Twist in the Tale

A Twist in the Tale As the Crow Flies

As the Crow Flies Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Only Time Will Tell

Only Time Will Tell Hell

Hell And Thereby Hangs a Tale

And Thereby Hangs a Tale The Short, the Long and the Tall

The Short, the Long and the Tall Cometh the Hour

Cometh the Hour Collected Short Stories

Collected Short Stories This Was a Man

This Was a Man Be Careful What You Wish For

Be Careful What You Wish For The Fourth Estate

The Fourth Estate Mightier Than the Sword

Mightier Than the Sword A Prisoner of Birth

A Prisoner of Birth Hidden in Plain Sight

Hidden in Plain Sight Nothing Ventured

Nothing Ventured Sons of Fortune

Sons of Fortune Too Many Coincidences

Too Many Coincidences The New Collected Short Stories

The New Collected Short Stories Cat O' Nine Tales: And Other Stories

Cat O' Nine Tales: And Other Stories The Eleventh Commandment

The Eleventh Commandment To Cut a Long Story Short (2000)

To Cut a Long Story Short (2000) Kane & Abel (1979)

Kane & Abel (1979) A Prison Diary Purgatory (2003)

A Prison Diary Purgatory (2003) False Impression (2006)

False Impression (2006) Only Time Will Tell (2011)

Only Time Will Tell (2011) A La Carte

A La Carte Cat O'Nine Tales (2006)

Cat O'Nine Tales (2006) The Eleventh Commandment (1998)

The Eleventh Commandment (1998) The Accused (Modern Plays)

The Accused (Modern Plays) Kane and Abel/Sons of Fortune

Kane and Abel/Sons of Fortune Heads You Win

Heads You Win In the Eye of the Beholder

In the Eye of the Beholder A Prison Diary

A Prison Diary Be Careful What You Wish For (The Clifton Chronicles)

Be Careful What You Wish For (The Clifton Chronicles) Tell Tale

Tell Tale The Collected Short Stories

The Collected Short Stories