- Home

- Jeffrey Archer

Heaven Page 4

Heaven Read online

Page 4

5.00 pm

I go off to the canteen for supper, and again sit at a table with two older prisoners. They are both in for fraud; one was a local councillor (three and a half months), and the other an ostrich farmer. The latter promises to tell me all the details when he has more time. It’s clear there’s going to be no shortage of good stories. Belmarsh — murder and GBH; Wayland — drug barons and armed robbers. NSC is looking a little more sophisticated.

7.00 pm

I join Doug in the hospital. He has allowed me to store a bottle of blackcurrant juice and a couple of bottles of Evian in his fridge, so I’ll always have my own supply. As Doug chats away, I learn a little more about his crime. He hates drug dealers, and considers his own incarceration a temporary inconvenience. In fact he plans a cruise to Australia just as soon as he’s released. On ‘the out’ he runs a small transport company. He has a yard and seven lorries, and employs — still employs — twelve people. He spends half an hour a day on the phone keeping abreast of what’s going on back at base.

Now to his crime; his export/import business was successful until a major client went bankrupt and renegued on a bill for £170,000, placing him under extreme pressure with his bank. He began to replenish his funds by illegally importing cigarettes from France. He received a two-year sentence for failing to pay customs and excise duty to the tune of £850,000.

DAY 93

FRIDAY 19 OCTOBER 2001

6.00 am

I write for two hours. Boxer shorts draped over the little light that beams down onto my desk ensure that I don’t disturb David.

8.15 am

I prepare identity cards for the three new prisoners who arrived yesterday. As each officer comes in, I make them tea or coffee. In between, I continue to organize the filing system for inductees. I will still be one myself for another week.

When Mr New arrives, he leaves his copy of The Times in the kitchen, and retrieves it at six before going home.

I am slowly getting into a routine. I now meet new prisoners as they appear, and find out what their problems are before they see an officer. Often they’ve come to the wrong office, or simply don’t have the right form. Many of them want to be interviewed for risk assessment, others need to see the governor, whose office is in the administration block on the other side of the prison. But the real problem is Mr New himself, because many prisoners believe that if their request doesn’t have his imprimatur, it won’t go any further. This is partly because he takes an interest in every prisoner, but mainly because he won’t rush them. He can often take twenty minutes to listen to their problems when all that is needed is for a form to be signed, which results in four other prisoners having to sit in the waiting room until he’s finished.

During any one day, about thirty prisoners visit SMU. I have to be careful not to overstep the mark, as inmates need to see me as fighting their corner, while the officers have to feel I’m helping to cut down their workload. I certainly need a greater mental stimulation than making cups of tea. But however much I take on, the pay remains 25p an hour, £8.50 a week.

12 noon

I pick up my lunch — vegetable pie and beans. No pudding. I take my tray back to the SMU and read The Times.

2.00 pm

A prisoner marches in and demands to be released on compassionate grounds because his mother is ill. Mr Downs, a shrewd, experienced officer, tells him that he’ll send a probation officer round to see his mother, so that they can decide if he should be released. The prisoner slopes off without another word. Mr Downs immediately calls the probation officer in Leicester, just in case the prisoner does have a sick mother.

Bob (lifer) comes to see the psychiatrist, Christine. Bob is preparing for life outside once he’s released, possibly next year, but before that can happen, he has to complete ten town visits without incident. Once he’s achieved this, he will be allowed out at weekends unescorted. The authorities will then assess if he is ready to be released. Bob has been in prison for twenty-three years, having originally been sentenced to fifteen. But as Christine points out, however strongly she recommends his release, in the end it is always Home Office decision.

Christine joins me in the kitchen and tells me about a lifer who went out on his first town visit after twenty years. He was given £20 so he could get used to shopping in a supermarket. When he arrived at the cash till and was asked how he would like to pay, he ran out leaving the goods behind. He just couldn’t cope with having to make a decision.

‘We also have to prepare all lifers for survival cooking.’ She adds, ‘You have to remember that some prisoners have had three cooked meals a day for twenty years, and they’ve become so institutionalized they can’t even boil an egg.’

The next lifer to see Christine is Mike. After twenty-two years in prison (he’s forty-nine), Mike is also coming to the end of his sentence. He invites me to supper on Sunday night (chicken curry). He’s determined to prove that he can not only take care of himself, but cook for others as well.

5.00 pm

I walk over to the canteen and join Ron the fraudster and Dave the ostrich farmer for cauliflower cheese. Ron declares that the food at NSC is as good as most motorway cafés. This is indeed a compliment to Wendy.

6.00 pm

Mr Hughes (my wing officer) informs me I can move across to room twelve in the no-smoking corridor.

When I locate the room I find it’s filthy, and the only furniture is a single unmade bed, a table and a chair. I despair. I am so pathetic at times like this.

In the opposite cell is a prisoner called Alan who is cleaning out his room, and asks if he can help. I enquire what he would charge to transform my room so that it looks like his.

‘Four phonecards,’ he says (£8).

‘Three,’ I counter. He agrees. I tell him I will return at eight-fifteen for roll-call and see how he’s getting on.

8.15 pm

I check in for roll-call before going off to see my new quarters. Alan has taken on an assistant, and they are slaving away. While Alan scrubs the cupboards, the assistant is working on the walls. I tell them I’ll return at ten and clear my debts. The only trouble is that I don’t have any phonecards, and won’t have before canteen on Wednesday. Doug comes to my rescue and takes over Darren’s role of purveyor of essential goods.

Doug appears anxious. He tells me that his fourteen-year-old daughter has suffered an epileptic fit. He’s being allowed to go home tomorrow and visit her.

We settle down to watch the evening film, and are joined by the senior security officer, Mr Hocking. He warns me that a News of the World journalist is roaming around the grounds but, with a bit of luck, will fall into the Wash. Just before he leaves, he asks Doug if he’s on home leave tomorrow.

‘Yes, I’m off to see my daughter, back by seven,’ Doug confirms.

‘Then we’ll need someone to be on duty after sister leaves at one. We mustn’t forget how many drugs there are in this building. Would you be willing to stand in as temporary hospital orderly, Jeffrey?’ he asks.

‘Yes, of course,’ I reply.

10.00 pm

I return to the north block for roll-call, before checking my room. I don’t recognize it. It’s spotless. I thank Alan, who takes a seat on the corner of the bed

He tells me that he has a twelve-month sentence for receiving stolen goods. He owns two furniture shops, in Leicester whose turnover last year was a little over £500,000, showing him a profit of around £120,000. He has a wife and two children, and between them they’re keeping the business ticking over until he has completed his sentence in four weeks’ time. It’s his first offence, and he certainly falls into that category of ‘never again’.

10.45 pm

I spend my first night at NSC in my own room. No music, no smoke, no hassle.

DAY 94

SATURDAY 20 OCTOBER 2001

6.00 am

Weekends are deadly in a prison. Jules, my pad-mate at Wayland used to say the only time you’re not

in prison is when you’re asleep. So over the weekend, a lot of prisoners just remain in bed. I’m lucky because I have my writing to occupy me.

8.00 am

I spot Matthew, who must have returned from Canterbury last night. His father is still in a coma, and he accompanies me to the office so he can phone the hospital. Although my official working week is Monday to Friday, it’s not unusual for an officer to be on duty at SMU on a Saturday morning.

Mr Downs and Mr Gough are already at their desks, and after I’ve made them both a cup of tea, Matthew takes me through my official duties for any given day or week. If I were to stick to simply what was required, it would take me no more than a couple of hours each day.

Over a cup of tea (Bovril for me), Matthew tells me about his nightmare year.

Matthew is twenty-four, six foot one, slim, dark-haired and handsome without being aware of it. He’s highly intelligent, but also rather gauche, and totally out of place in prison. He read marine anthropology at Manchester University and will complete his PhD once he’s released. I ask him if he’s a digger or an academic. ‘An academic,’ he replies, without hesitation.

His first job after leaving university was as a volunteer at a museum in his home town. He was happy there, but soon decided he wanted to return to university. That was when his mother contracted MS and everything began to go badly wrong. After his mother was bedridden, he and his sister took it in turns to help around the house, so that his father could continue to work. All three found the extra workload a tremendous strain. One evening while at work in the museum, Matthew took home some ancient coins to study. I haven’t used the word ‘stole’ because he returned all the coins a few days later. But the incident weighed so heavily on his conscience that he informed his supervisor. Matthew thought that would be the end of the matter. But someone decided to report the incident to the police. Matthew was arrested and charged with breach of trust. He pleaded guilty, and was assured by the police that they would not be pushing for a custodial sentence. His solicitor was also of the same opinion, advising Matthew that he would probably get a suspended sentence or a community service order. The judge gave him fifteen months.5

Matthew is a classic example of someone who should not have been sent to jail; a hundred hours of community service might serve some purpose, but this boy has spent the last three months with murderers, drug addicts and burglars. He won’t turn to a life of crime, but how many less intelligent people might? It’s a rotten system that allows such a person to end up in prison.

My former secretary, Angie Peppiatt, stole thousands of pounds from me, and still hasn’t been arrested. I feel for Matthew.

12 noon

Lunch today is just as bad as Belmarsh or Wayland. Matthew explains that Wendy is off. I must remember to eat only when Wendy is on duty.

2.00 pm

I report to the hospital and take over Doug’s caretaker role, while he visits his daughter. I settle down with a glass of blackcurrant juice and Evian to watch England slaughter Ireland, and win the Grand Slam, the Triple Crown and … after all, we are far superior on paper. Unfortunately, rugby is not played on paper but on pitches. Ireland hammer us 20-14, and return to the Emerald Isles with smiles on their faces.

I’m still sulking when a tall, handsome black man strolls in. His name is Clive. I only hope he’s not ill, because if he is, I’m the last person he needs. He tells me that he’s serving the last third of his sentence, and has just returned from a week’s home leave — part of his rehabilitation programme.

Clive and I are the only two prisoners who have the privilege of visiting Doug in the evenings. I quickly discover why Doug enjoys Clive’s company. He’s bright, incisive and entertaining and, if it were not politically incorrect, I would describe him as sharp as a cartload of monkeys. Let me give you just one example of how he works the system.

During the week Clive works as a line manager for a fruit-packing company in Boston. He leaves the prison after breakfast at eight and doesn’t return until seven in the evening. For this, he is paid £200 a week. So during the week, NSC is no more than a bed and breakfast, and the only day he has to spend in prison is Sunday. But Clive has a solution for that as well.

Two Sundays in every month he takes up his allocated town visits, while on the third Sunday he’s allowed an overnight stay.

‘But what about the fourth or fifth Sunday?’ I ask.

‘Religious exemption,’ he explains.

‘But why, when there’s a chapel in the grounds?’ I demand.

‘Your chapel is in your grounds,’ says Clive, ‘because you’re C of E. Not me,’ he adds. ‘I’m a Jehovah’s Witness. I must visit my place of worship at least one Sunday in every month, and the nearest one just happens to be in Leicester.’

After a coffee, Clive invites me over to his room on the south block to play backgammon. His room turns out not to be five paces by three, or even seven by three. It’s a little over ten paces by ten. In fact it’s larger than my bedroom in London or Grantchester.

‘How did you manage this?’ I ask, as we settle down on opposite sides of the board.

‘Well, it used to be a storeroom,’ he explains, ‘until I rehabilitated it.’

‘But it could easily house four prisoners.’

‘True,’ says Clive, ‘but remember I’m also the race relations representative, so they’ll only allow black prisoners to share a room with me. There aren’t that many black prisoners in D-cats,’ he adds with a smile.

I hadn’t noticed the sudden drop in the black population after leaving Wayland until Clive mentioned it. But I have seen a few at NSC, so I ask why they aren’t allowed to room with him.

‘They all start life on the north block, and that’s where they stay,’ he adds without explanation. He also beat me at backgammon — leaving me three Mars Bars light.

DAY 95

SUNDAY 21 OCTOBER 2001

6.00 am

Sunday is a day of rest, and if there’s one thing you don’t need in prison it’s a day of rest.

8.00 am

SMU is open as Mr Downs is transferring files from his office to the administration block before taking up new responsibilities. Fifteen new prisoners arrived on Friday, giving me an excuse to prepare files and make up their identity cards.

North Sea Camp, whose capacity is 220, rarely has more than 170 inmates at any one time. As inmates have the right to be within fifty miles of their families, being stuck out on the east coast limits the catchment area. Two of the spurs are being refurbished at the moment, which shows the lack of pressure on accommodation.6 The turnover at NSC is about fifteen prisoners a week. What I am about to reveal is common to all D-cat prisons, and by no means exclusive to NSC. On average, one prisoner absconds every week (unlawfully at large), the figures have a tendency to rise around Christmas and drop a little during the summer, so NSC loses around fifty prisoners a year; this explains the need for five roll-calls a day. Many absconders return within twenty-four hours, having thought better of it; they have twenty-eight days added to their sentence. A few, often foreigners, return to their countries and are never seen again. Quite recently, two Dutchmen absconded and were picked up by a speedboat, as the beach is only 100 yards out of bounds. They were back in Holland before the next roll-call.

Most absconders are quickly recaptured, many only getting as far as Boston, a mere six miles away. They are then transferred to a C-cat with its high walls and razor wire, and will never, under any circumstances, be allowed to return to an open prison, even if at some time in the future they are convicted of a minor offence. A few, very few, get clean away. But they must then spend every day looking over their shoulder.

There are even some cases of wives or girlfriends sending husbands or partners back to prison, and in one case a mother-in-law returning an errant prisoner to the front gate, declaring that she didn’t want to see him again until he completed his sentence.

This is all relevant because of something that took

place today.

When granted weekend leave, you must report back by seven o’clock on Sunday evening, and if you are even a minute late, you are placed on report. Yesterday, a wife was driving her husband back to the prison, when they became involved in a heated row. The wife stopped the car and dumped her husband on the roadside some thirty miles from the jail. He ran to the nearest phone box to let the prison know what had happened and a taxi was sent out to pick him up. He checked in over an hour late. Thirty pounds was deducted from his canteen account to pay for the taxi, and he’s been placed on report.

2.00 pm

I go for a two-mile walk with Clive, who is spending a rare Sunday in prison. We discuss the morning papers. They have me variously working on the farm/in the hospital/cleaning the latrines/eating alone/lording it over everyone. However, nothing beats the Mail on Sunday, which produces a blurred photo of me proving that I have refused to wear prison clothes. This despite the fact that I’m wearing prison jeans and a grey prison sweatshirt in the photo.

A Matter of Honor

A Matter of Honor Four Warned

Four Warned A Quiver Full of Arrows

A Quiver Full of Arrows Not a Penny More, Not a Penny Less

Not a Penny More, Not a Penny Less To Cut a Long Story Short

To Cut a Long Story Short The Gospel According to Judas by Benjamin Iscariot

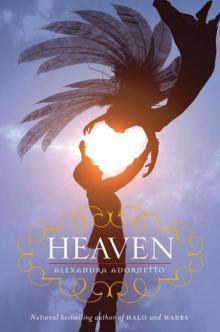

The Gospel According to Judas by Benjamin Iscariot Heaven

Heaven First Among Equals

First Among Equals Purgatory

Purgatory Kane and Abel

Kane and Abel Honor Among Thieves

Honor Among Thieves Shall We Tell the President?

Shall We Tell the President? The Prodigal Daughter

The Prodigal Daughter False Impression

False Impression Paths of Glory

Paths of Glory A Twist in the Tale

A Twist in the Tale As the Crow Flies

As the Crow Flies Best Kept Secret

Best Kept Secret Only Time Will Tell

Only Time Will Tell Hell

Hell And Thereby Hangs a Tale

And Thereby Hangs a Tale The Short, the Long and the Tall

The Short, the Long and the Tall Cometh the Hour

Cometh the Hour Collected Short Stories

Collected Short Stories This Was a Man

This Was a Man Be Careful What You Wish For

Be Careful What You Wish For The Fourth Estate

The Fourth Estate Mightier Than the Sword

Mightier Than the Sword A Prisoner of Birth

A Prisoner of Birth Hidden in Plain Sight

Hidden in Plain Sight Nothing Ventured

Nothing Ventured Sons of Fortune

Sons of Fortune Too Many Coincidences

Too Many Coincidences The New Collected Short Stories

The New Collected Short Stories Cat O' Nine Tales: And Other Stories

Cat O' Nine Tales: And Other Stories The Eleventh Commandment

The Eleventh Commandment To Cut a Long Story Short (2000)

To Cut a Long Story Short (2000) Kane & Abel (1979)

Kane & Abel (1979) A Prison Diary Purgatory (2003)

A Prison Diary Purgatory (2003) False Impression (2006)

False Impression (2006) Only Time Will Tell (2011)

Only Time Will Tell (2011) A La Carte

A La Carte Cat O'Nine Tales (2006)

Cat O'Nine Tales (2006) The Eleventh Commandment (1998)

The Eleventh Commandment (1998) The Accused (Modern Plays)

The Accused (Modern Plays) Kane and Abel/Sons of Fortune

Kane and Abel/Sons of Fortune Heads You Win

Heads You Win In the Eye of the Beholder

In the Eye of the Beholder A Prison Diary

A Prison Diary Be Careful What You Wish For (The Clifton Chronicles)

Be Careful What You Wish For (The Clifton Chronicles) Tell Tale

Tell Tale The Collected Short Stories

The Collected Short Stories